The workshop “Participatory Evaluation in Citizen Science” was organised in the context of the CitSciVirtual conference of the (mainly US-based) Citizen Science Association. It started from the observation that while Citizen Science is highly participatory, evaluation does not live up to this claim. Consequently, the ambition was to collaboratively tackle this theoretical and methodological gap and further develop existing approaches in the context of a practical Citizen Science case simulation.

The workshop was preceded by sharing materials outlining the host’s approach to participatory evaluation or “co-evaluation”, including a video and readings on the matter, as well as a pre-survey to collect the experiences and expectations of participants. The interactive virtual session on the 12th of May 2021 offered a limited number of participants a space for in-depth discussion and exchange. Structurally, the live session included a brief refresher on participatory evaluation (see presentation slides: https://zenodo.org/record/4820791), followed by collaborative case work in breakout groups. The results of these breakout groups were then reported in the plenary, where open questions were collected for future investigations.

|

Min

|

Section

|

Description

|

|

5

|

Arrival and Welcome

|

Short introductory round and welcome

|

|

15

|

Introduction

|

Brief introduction to the workshop and participatory evaluation in citizen science.

|

|

40

|

Breakout Groups

|

Case simulation: Participants discuss potential participatory evaluation approaches, addressing challenges and benefits of such participatory formats along the co-evaluation principles within the framework of a fictional Citizen Science case.

|

|

20

|

Plenary Discussion

|

Reuniting after breakout groups, each group reports the main points of their debate.

|

|

10

|

Feedback and Sendoff

|

|

In the brief introduction, the workshop hosts discussed how different dimensions of evaluation in Citizen Science might be made tangible, specifically focussing on the open framework developed by Kieslinger et al. (2018). Here, evaluation is conceptually divided into formative (process and feasibility) and summative (outcome and impact) evaluation and further distinguished by three levels: Scientific, participant, and socio-ecological & economic. Listing typical (quantitative) key performance indicators applied in such contexts, the hosts then reframed evaluation in a participatory, bottom-up way that gives voice to the stakeholders of an intervention and involve them more closely in decision-making processes. Such a co-evaluative approach initiates the conversation on expectations, objectives and impact already at the start of the project, involving participants in the decision on project goals as well as evaluation instruments.

Six Principles of Co-Evaluation

Adapting the “Utilization-Focused Evaluation” framework from Patton (2008) to the context of participatory evaluation, the hosts introduced six principles that should guide the implementation of a co-evaluation, before presenting concrete examples of methodologies that can be employed in such a context.

|

Participant ownership

|

Evaluation is oriented to the needs of the participants in an inclusive and balanced way. Participants take certain actions and responsibilities for project outcomes and their assessment.

|

|

Openness and reflexivity

|

Participants meet to communicate and negotiate to reach a consensus on evaluation results, solve problems, and make plans for the improvement of the project, evaluation approaches, and impact measures; input should be balanced and representation should be guaranteed for all involved stakeholders

|

|

Transformation

|

Emphasis is on identification of lessons learned, improvement of benefits and wellbeing, for all participants.

|

|

Flexibility

|

Co-evaluation design is flexible and determined (to the extent possible) during the group processes. The mix of formats and methods used should reflect the project aims and potentially empower marginalised perspectives.

|

|

Documentation and transparency

|

Whenever possible and ethically desirable, evaluation procedures should be documented and made accessible to participants, or even the wider public.

|

|

Timing

|

Co-evaluation has to start as early as possible, but latest during the negotiation of research questions and design of methodology.

|

Case Simulation: Hog Farm Community Science

As a framing for the collaborative work, we elaborated a fictional Citizen Science case. In clearly defining the setting, involved actors, concerns and methodologies, the focus was then put on discussing entry-points and potential instruments for implementing a participatory evaluation.

|

Case Description

|

|

Kaneesha is living next to a major hog farm and has been concerned with the air, water and odour pollution from the farm for a while. Furthermore, other residents have observed several violations of animal rights, and have heard of terrible working conditions. Numerous complaints to the company running the farm, to local administration and responsible politicians had achieved nothing. Together with other resident activists in her area, they organised an effort to monitor for pollution one year ago. Building on literature from citizen science, they contacted the local community college to initiate a monitoring action and to create tools to systematically collect information about the situation.

The whole initiative grew fast into a community building and local activist experiment. Kaneesha and the others wanted to create a systematic and transparent participatory process, being inclusive to many voices in the area. Using instructions on the web and support from other groups, they have created a Do-It-Yourself aerosol sampler, which allows them to capture the spray from the farm that is reaching their neighbourhood. The content of the aerosol is analysed in the local college, together with teachers and students. Furthermore, the activists invited scientists from a university nearby to test the validity of their methods and results.

Moreover, Kaneesha and the local activist group used a whole array of systematic methods to document also the wider context of the problem, besides building a measuring device and collecting pollution data.

Information about the pollution and reports about health impacts and personal stories from residents about their health conditions and environmental observations were used to make the case for environmental harm to the state environmental authority. Although they are now receiving more Although they are now receiving more attention due to the strong evidence base, and the case is attracting media attention, the process is dragging on longer than expected. Moreover, the relationship with the farming company became very difficult as they were not involved in the citizen science investigations and now appear even more uncooperative. Last but not least, some residents also working at the hog farm are in a moral dilemma, since they are both deeply affected by the pollution and would like to engage more, while also fearing a loss of their jobs.

The resident activists want to use the time to learn from their own process, having been too busy during it. Did they do everything right? What could they do better? And how could they best package their knowledge so that other activists can learn from it? How could they maximise their impact, while creating better living conditions?

|

|

Setting

|

|

Involved people:

Concerns:

-

Pollution

-

Environmental justice

-

Worker’s rights

-

Animal welfare

-

…

|

|

Methodologies

|

-

Biographical interviews with locals about their problems

-

Systematic monitoring in the form of environmental justice diaries

-

Collective data analysis and interpretation

-

Translation of results into presentable information for different stakeholders (including the farming company)

-

Documentation of the process and creation of an association to receive funding and become a legal entity

-

Creation of a logic model for evaluation, to better understand the input, the process, the outcomes, the outputs and the potential impact and to better align their strategy

|

Work in Breakout Groups

Within the context of this elaborate fictional case, the participants were divided into two groups and asked to discuss with the workshop hosts a set of questions aimed at scrutinising potential settings and instruments for a co-evaluation:

-

What approaches do you think are most promising for designing a robust and participatory evaluation here?

-

Which tools/settings could be used?

-

Which of the 6 co-evaluation principles are particularly important to consider in this case?

-

Who would have been the most important stakeholders to involve?

-

How could the different expectations and needs be better included throughout the process?

-

Which channels for reflection and feedback could have been implemented from the beginning?

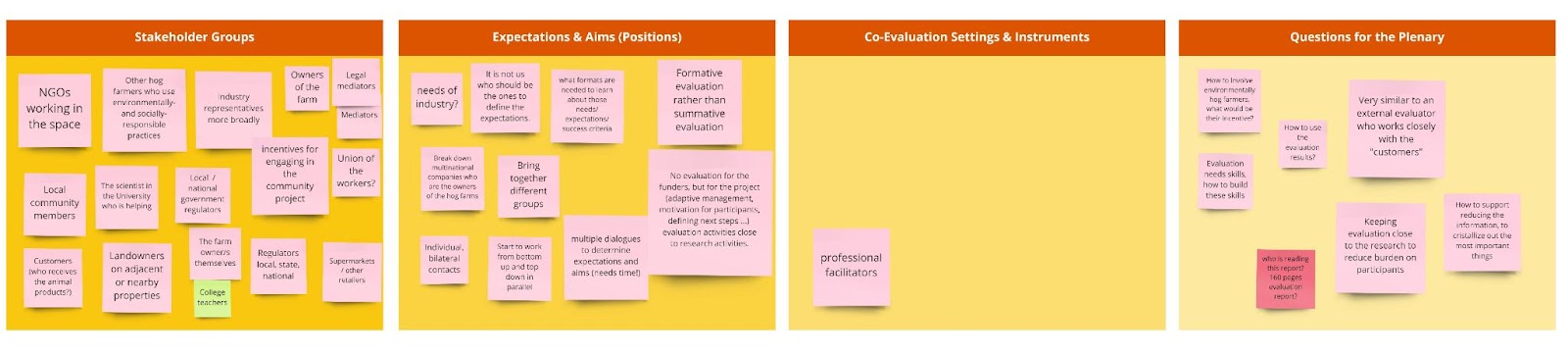

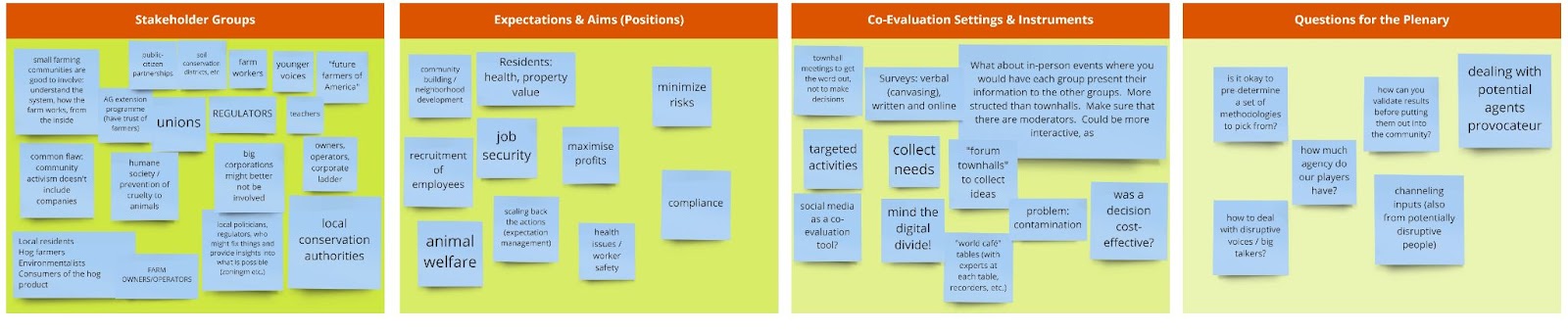

To facilitate the discussion, the hosts prepared a Miro board structured along four categories: 1) potential stakeholder groups affected by the case; 2) expectations and aims these stakeholders might bring to the table; 3) possible co-evaluation settings and instruments arising from these; and 4) questions to bring to the plenary.

Learnings

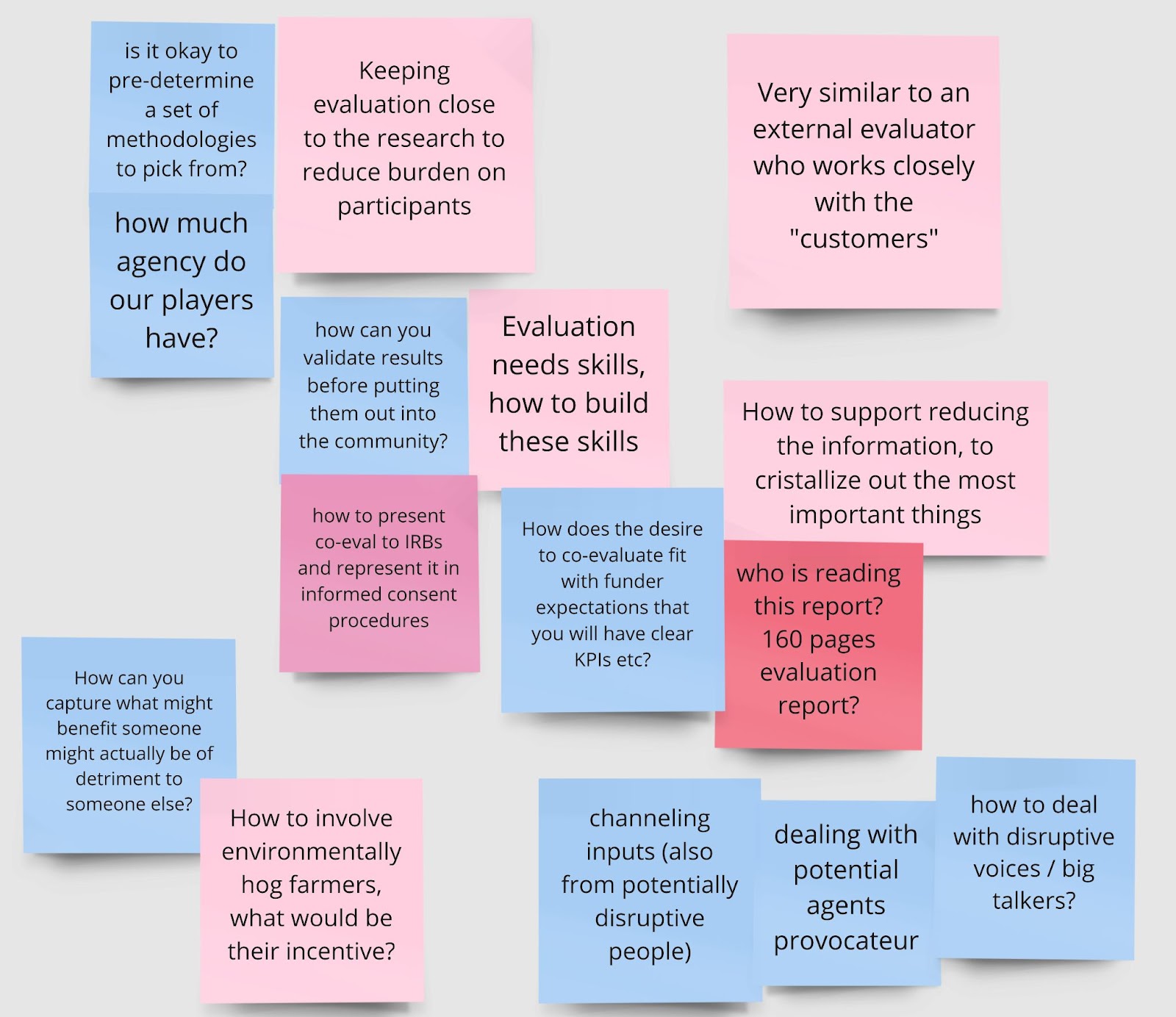

While collectively discussing the intricacies of the case, a number of themes emerged. Looking at co-evaluation from the perspective of the academic system, the role of institutional review boards (IRBs) as gatekeepers was brought up. As participatory evaluation processes demand a lot of flexibility, they might not fit within the legal and organisational structures demanded within scientific organisations. Similarly, research funders have expectations of clear and quantifiable KPIs that might not allow for an approach of co-defining measures of success with participants. Co-evaluation might furthermore be hard to represent in informed consent procedures, which impacts not just IRB procedures, but might complicate the collaboration with citizen participants.

Altogether, the complexity of the scientific process was seen as a potential burden on participants that demands for careful calibration. Questions of how to build the skills to enable co-evaluation, to validate inputs before putting them out into the community, but also of how to support the reduction of information and crystallizing the most important things were brought up. One proposed solution to this set of problems was to keep the evaluation close to the research and thus reduce the burden on participants, although the question of how to accomplish this goal was left open. In a similar vein, the validity of pre-determining a set of methodologies to pick from was brought up, which also touches on the question of how much agency groups of participants have in a given process. It was also agreed that a lengthy and complicated evaluation report was not an appropriate result of a participatory evaluation and different formats should be considered.

The final thematic cluster touched on the question of how to bridge the diverse and often diverging goals and needs between different stakeholders such as investors, hog farmers, workers, residents, academic scientists, and so on, noting that the solutions and needs of some stakeholders might be detrimental to those of others. Although they may have different standpoints, the inclusion of the diverse stakeholders of an intervention turned out to be essential, as contrarian voices might resort to sabotaging a process from the outside if excluded. For instance, workshop participants shared how the exclusion of corporate actors in similar existing projects led to their disruptive self-involvement in the form of agents provocateurs, attempts at intimidation, and more generally the use of financial funds to undermine the projects. In any case, managing the expectations of different actors is essential for the success of a project.

The participants also proposed some methodologies that allow for the collecting and constructive discussion of different needs, such as forum town hall meetings and “world café”-style workshops with experts or professional facilitators guiding discussions at each table.

While the workshop participants agreed that more time for discussion would have been helpful, the most important feedback for the hosts was that thinking through the benefits and challenges of participatory evaluation via concrete experiences helps in understanding and tackling such an endeavour. Furthermore, it became clear that an extended workshop format needs to be considered in the future, offering the opportunity to reflect on concrete methods and streams of experience.

References

Kieslinger, B., Schäfer, T., Heigl, F., Dörler, D., Richter, A., & Bonn, A. (2018). Evaluating citizen science: Towards an open framework. In S. Hecker, M. Haklay, A. Bowser, Z. Makuch, J. Vogel, & A. Bonn (Eds.), Citizen science – Innovation in open science, society and policy (pp. 81-98). London: UCL Press.

Patton, Michael Quinn.(2008) Utilization-Focused Evaluation: 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, Ca: Sage Publications.